You would have thought that an artist as transparently great as Rembrandt would always have been appreciated. How could greatness as obvious as his be missed? But taste often needs to go to Specsavers, and various stretches of cultural history have successfully overlooked the master. Even during his lifetime, he was in favour, then out. And since his death in 1669, the mood has continued to fluctuate. Except in Britain, where the love of Rembrandt has remained firm and fierce.

That, at least, is the story told to us by Rembrandt: Britain’s Discovery of the Master, a well-meaning show at the Scottish National Gallery that aims to be the cornerstone of your art adventures in Edinburgh this summer. If you saw the thrilling Charles I exhibition earlier this year at the Royal Academy, in London, you will already know that the first Rembrandts in Britain were presciently acquired by Charles in the 1630s. One of them was the so-called portrait of the artist’s mother, which is still in the Royal Collection. The other was the youthful self-portrait on show here: Rembrandt in his early twenties, staring out from a painted oval, long-haired and sporting a beret, wrapped in a thick fur coat, firing his palpable humanity at us from both barrels.

With Rembrandt, time is an irrelevance. He was then. We are now. But that doesn’t stop him being right in front of us: breathing, looking, thinking. It’s a connection you find nowhere else in art. There are other geniuses who bring you close to a sitter — Holbein, Dürer, Caravaggio — but none of them throws in this kissing of minds: Rembrandt’s psychological intimacy.

The present show skips briskly past Charles and his pioneering taste for the master. Instead, the point is made here that the king was merely a receiver of Dutch gifts, rather than an active admirer. I’m not sure how that squares with the fact that Rembrandt’s wrinkly portrait of his mother used to hang in the king’s private cabinet in Whitehall, where he had to pass it on a daily basis. But one thing this is not is a soppy show, and those of us who like our Rembrandt warm and fuzzy are forced to take a sober and scholarly walk through an event that puts prose ahead of poetry.

It turns out that Britain’s most impactful contribution to the Rembrandt story concerned not his paintings, but his prints. Charles may have presciently acquired the first portraits, but it was the brilliant assortment of etchings pumped out by the Rembrandt factory in Amsterdam that most actively spread the master’s example and fame.

It’s a development set mostly in the 18th century. The age of Charles I may have peeped at Rembrandt, and collected him here and there, but it was the booming art market of Georgian England that turned the mild interest into a mad craze. While Rembrandt’s paintings were rare and expensive, the prints were plentiful and affordable. Not only did the British appetite for them outstrip everyone else’s, it also took many forms.

Most obviously, it was evident in the busy accumulation of the master’s etchings. There are only two contenders for the title of greatest print-maker in art — Dürer and Rembrandt — and, although I myself sway marginally towards the former, I have no problem with the present exhibition’s insistence on the latter.

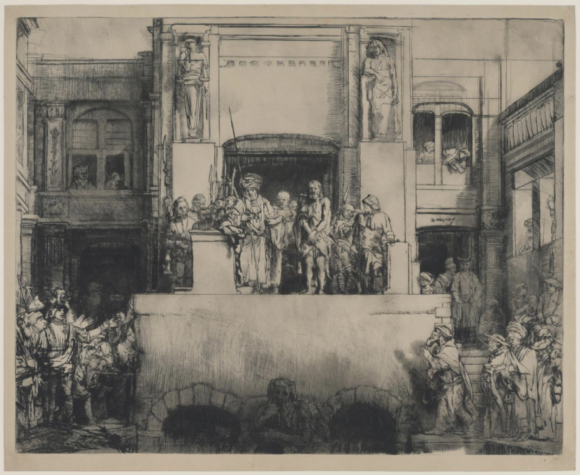

Rembrandt’s prints, represented here by copious and varied examples, are driven by a powerful sense of adventure. A new art form is being experimented with, developed, tested for speed. In the beautiful etching of The Three Trees, the lonely oaks on the hill utter not a single word of religion, but you know immediately that they refer to the three crosses of the crucifixion. This is an inescapable reading.

So his landscapes were filled with big moods and weighty implications, and the British landscape tradition learnt how to do that from him. But he was also an uncommonly sensitive portrayer of the female nude; a marvellous orchestrator of crowd scenes; a profound recorder of faces; a misty ruminator on deep religious meanings; a relentless investigator of himself. And all these different aspects of Rembrandt found a forum in his extraordinarily varied print-making.

There were so many prints to choose from. One pioneering 18th-century collector, remembered here, managed to acquire the entire catalogue of Rembrandt’s etchings; with extras and add-ons, he eventually collected about 420 images. Thus, the middle of this show has about it the geekish air of a cigarette-card fair where collections are completed, repeated and swapped.

So frantic was the 18th-century interest in Rembrandt’s prints that his authentic work no longer met the demand, and various forgeries, mirrorings and borrowings began to circulate. People began to reprint him in red. Rework him. Quote him. Add to him.

That beautiful painting in the Scottish National Gallery of a young woman in bed, peeping around a curtain, is probably a biblical scene: Sarah, wife of Tobias, has woken to find the angel Raphael come to save her from the demon of lust. But we don’t actually see Raphael. Just his divine light bathing the half-naked Sarah.

Once the lesser artists of 18th-century Britain got their hands on the image, however, they quickly set about shearing it of its religious profundity. In Richard Cooper’s pale drawing of 1781, Sarah has coyly become “Rembrandt’s Mistress”. In the next mezzotint, by William Dickinson, she is “Lydia”, a topless enchantress in a turban giving you the come-on with naughty eyes.

All this is intriguing, but I cannot say it sends the heart thumping. When the convoluted tale of Rembrandt’s prints and their versions pushes itself to the foreground of this show, it feels like a drop in intensity. I found myself searching out the painterly loans for a top-up of proper Rembrandtian power.

Belshazzar’s Feast, borrowed from London’s National Gallery, features brushwork so turbulent, it looks as if it was painted by a thunderstorm. The Mill, one of Rembrandt’s most haunting landscapes, loaned by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, is set in a twilight so atmospheric, you think you can hear the curlews calling.

Unfortunately, it is also noticeable that British tastes in Rembrandt — once his paintings became more available — were not especially adventurous. British collectors generally preferred his safer portraits, and didn’t appear to like it when Rembrandt grew too Rembrandty. I should also warn you that the lighting in the Scottish Academy building in which this show is housed is glaring and intrusive. The impressive loan of two huge portraits from Boston of Rembrandt’s only English sitters, the Rev John Elison and his wife, is undermined by the fact that you cannot see them properly.

Rembrandt, the master of light, deserves better. At his finest, his truest, he slaps and stirs your emotions, overwhelms you with his passion, assaults you with his paintwork. And that doesn’t happen often enough at this scholarly and sensible event.

Rembrandt: Britain’s Discovery of the Master, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, until Oct 14