Rejoice. Neil MacGregor, the nearest thing I know to a human deity, is back on the airwaves in a daily series on Radio 4 called Living with the Gods. MacGregor is as divinely good at being on the radio as he was at everything else he did in his brilliant curatorial past — running the National Gallery, running the British Museum. He’s good because he understands the power of an oral tradition and recognises how a story whispered intimately on the radio lodges itself deeper into the imagination than stories told in other ways. In the old days, we gathered around the hearth to hear the village elder or Homer or grandad fill our thoughts with important societal wisdoms. Today, we gather around the portable hearth that is Radio 4 to hear MacGregor tell us why we believe in gods and where those beliefs have led us.

Living with the Gods, the radio series, does what all MacGregor’s radio work has done: it uses art to help us understand our human past. It’s an approach that encourages him to focus on meaningful objects rather than masterpieces, and to privilege telling contexts over grand or expensive ones. For MacGregor, a humble thimble can hold as much religious truth as the Sistine Chapel. It’s a marvellous attitude, and it doesn’t only make for powerful radio, it also makes for fascinating exhibitions.

Living with Gods, at the British Museum, the radio show made flesh, is an absurdly brave attempt to tell the story of human belief — all of it, the whole shebang, from day one until today — through a telling assemblage of objects. It’s absurdly brave because it is so boundless in scope and because no one reading this article will be in any doubt about the fractious and delicate nature of such a display. When it comes to the stories of the gods and the religions that contain them, there are no fixed divides between the meats and the poisons. There is only the constant possibility of mistaking one for the other.

This is, therefore, a task packed with dangers. Why attempt it? Because another of the curatorial ambitions that make Neil MacGregor semi-divine is his desire to make the ancient treasures of the British Museum fully relevant to the modern world. It’s an attitude he exhibited relentlessly while director; and now he has left, he continues to exhibit it in his new role as the ghost that haunts the BM battlements: Banquo MacGregor, conscience of the nation.

The first object we see here, and the first object examined on the radio, is the so-called Lion Man, an ivory carving, dated to about 40,000 years ago, showing an upright figure with the head of a lion. It’s a spooky icon, as strict and staring as an Egyptian Horus or a Greek kouros. The sculptural language being spoken here is a language with a potent artistic future.

The Lion Man is said to be the first known image of a god — the first amalgam of human and animal features. To me, it remains possible that he could be a man wearing a lion mask or, indeed, an upright cave lion. But the most salient fact about him — that he played a religious role — is indisputable. This was clearly a piece of art with sacred ambitions. Forty thousand years ago, art was so important to the workings of human society that the need was felt to carve this figure out of a mammoth tusk, to place it at the back of a cave, and to gather before it on ritual occasions and direct religious feelings towards it.

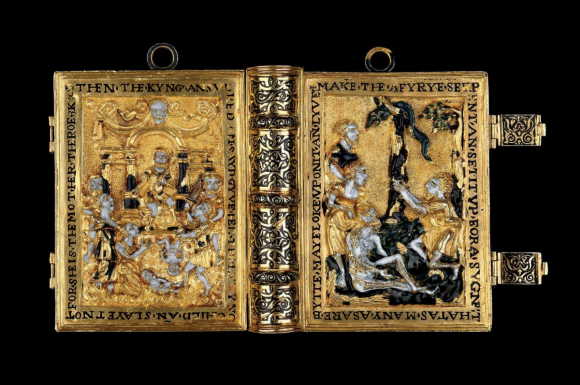

By imagining the gods and giving them a recognisable artistic form — by imagining the unimaginable — art was performing a crucial societal service and making itself internationally indispensable. So the show ahead skips happily from religion to religion as it investigates the shared artistic ambitions of the world’s faiths.

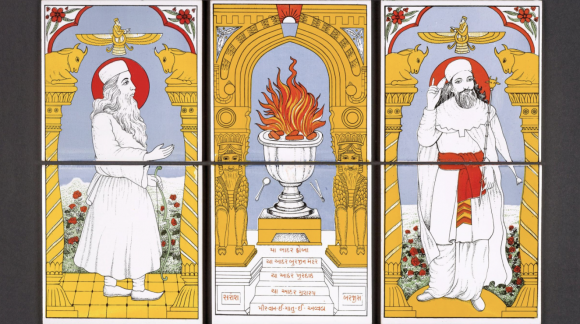

A section devoted to light, water and fire reveals how various religions, from Shinto to Buddhism, from Islam to Zoroastranism, from Christianity to Hinduism, found different ways to celebrate these elemental forces. Thus a 14th-century mosque lamp from Syria inscribed with lines from the Koran — “Allah is the Light of the heavens and the earth” — sits alongside a Japanese woodcut telling the story of Amaterasu, the Japanese goddess of the sun, who was lured out of a cave by erotic laughter and then filled the world with light.

Fire, with its mysterious flickerings and ineffable power, bringer of life and death, is another religious ubiquity. For the delightful Shiva Nataraja, dancing in a ring of flames, fire is the beginning and the end, the creation and the destruction. Which is why an image of him stands outside the Cern nuclear research centre in Switzerland.

All this is excellent storytelling. For a religious show, this event feels thoroughly unpreachy. By seeing religion through the magnifying glass of art, the journey seems also to step out in surprising directions. Who would have thought that Mahatma Gandhi would come in for such a bashing in the story of Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, the heroic Untouchable who converted to Buddhism when the high Brahmin cult of Gandhi refused to sanction his equality? In 2012, Ambedkar, not Gandhi, was voted “the greatest Indian”.

The section dealing with the senses and the way religious truths enter us through smells, sounds and touches is particularly inventive and plangent. Every religion has its incense burners and its communal chants, its sacred foods and its holy smells. “God gave us music that we may pray without words,” explains a helpful wall text, quoting St Augustine of Hippo. Just as the primitive origins of fire seem to link us to the earliest religious circumstances, so the foregrounding here of the senses feels as if it is addressing an especially deep religious truth.

Another point cleverly made is how the peripatetic impulse for religion keeps jumping boundaries; indeed, we shouldn’t see boundaries as boundaries, but as points of connection. Thus we learn that the various religious beads laid out carefully in a vitrine as aids to prayer originated in Buddhism, migrated to Christianity and ended up in Islam.

This is not just a collection of old objects explaining the religious impulse. It is also a collection of religious objects seeking fiercely to heal the religious rifts that have opened up in our world. The overall message of the show — that human beings are hardwired to have religious beliefs, that the details of those beliefs may separate us, but the essentials unite us — is a typical MacGregor message aimed not only at art lovers but at news broadcasts and Panorama specials; at imams and rabbis, Lutherans and popes, the north of Ireland and the south, Sunni and Shiite.

Every object on display here whispers the same huge cosmic truth: we think we’re different, but we’re actually the same.

Living with Gods, British Museum, London WC1, until April 8; BBC Radio 4, weekdays, 9.45am