Only rarely in my time as an art reviewer have I felt as flabbergasted as I was by the watercolours of Georgiana Houghton. Her dates had me rubbing my eyes in disbelief. She did this when? Out of nowhere, like an unforeseen comet, a career has appeared in art that rewrites the whole story.

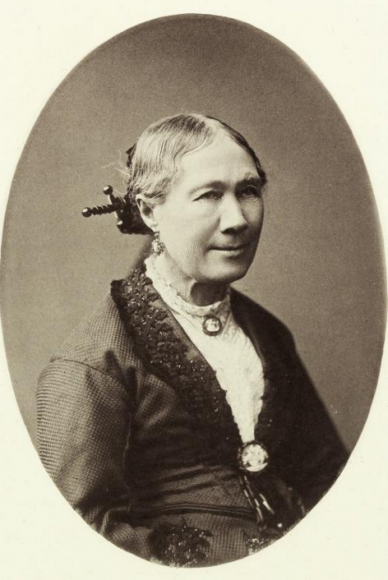

Houghton (1814-84) was in most ways a typical Victorian presence. Born into a large middle-class family — seven children and counting — she was left stranded when her father’s business went belly up and she found herself forced into a life of “genteel poverty”. Having tested her resolve with money issues, the fates began now to beat her about the head with death. Her brother, Cecil Angelo, died in 1826, aged nine. Her especially beloved sister, Zilla Rosalia, went in 1851, aged 31. Georgiana herself never married. She became that saddest of societal offcuts: a Victorian spinster.

While her father still had money, she had trained as an artist, but at the death of Zilla, who was apparently a “charming artist” herself, Georgiana renounced art. Instead, she turned for comfort to a new craze that had recently arrived in Britain from America and was taking the sitting rooms of the lonely by storm: spiritualism. In 1859, she attended her first séance. Within three months, she had made herself expert enough at operating the ouija board to conduct her own paranormal events. From now on, she wrote in her memoir, her aim in life was “to show what the Lord hath done for my soul by granting me the Light now poured upon mankind by the restored power of communion with the unseen”. And that’s where the art came in.

During her séances, Georgiana found herself talking first to Zilla, then to someone called Henry Lenny (no joke: that was his name), who described himself as “a deaf and dumb artist”. Henry encouraged her to become his conduit. Putting her hands at his disposal, she commenced production of the staggering collection of little pictures unveiled to us now by the Courtauld Gallery.

They are staggering because they move back the invention of abstraction from circa 1910, when Kandinsky was said to have set art on a new path with his first “non-representative” paintings, to 1861, when Houghton produced The Holy Trinity, a dark crisscrossing of red and blue lines up and down the paper that then go left to right, then down again in twists and spirals, and up once more in energetic slashes, a working and reworking of energy fields so layered and physical that it can accurately be described as action painting. Action painting, remember, is something Jackson Pollock was said to have invented in the 1940s.

Having learnt from Henry Lenny that her hands were the medium through which the spirit world wished to instruct the Victorian age on the dynamics of progressive abstraction, Houghton spent the rest of the 1860s spewing out gorgeous watercolours of increasing delicacy and complexity. With their busy swirls of light and movement, they are often reminiscent of Italian futurism, which they prefigure by 50 years. The futurists were trying to convey the electric pulse and mechanical speed of the 20th century. Houghton beat them to it with an art that sought to give physical form to the throbs and flutters flowing through her from the spirit world.

Because she had trained as an artist, the quality of her spirit “guides” was also impressive. An especially dense cluster of beautiful spirals that buzz about the picture like a swarm of bees trapped in a jar was sent “through the hand of Georgiana” by no less a figure than Titian. The Eye of God, a fiery surfing wave of yellows and reds hurtling from left to right, was the spiritual handiwork of Correggio. A picture called The Sheltering Wing of the Most High, in which a delicate tracery of phantasmagorical white lines is sometimes there, sometimes not there, like a jellyfish in the water, was transported to us, via Houghton, by Sir Thomas Lawrence, who was seeking to symbolise “the marvellous love of God”.

With these celebrated Old Masters guiding her hand, Houghton grew ever more assured. On the back of every picture, she carefully spelt out her symbolic ambitions for the image overleaf, but only in one instance, where the face of a distinctly feminine Jesus pops up suddenly in the middle of the swirls, does her art actually feel churchy or cultish. Take away the titles and you have a pure abstraction that is being invented a century before its time.

The works on show come mostly from Melbourne, where a cardboard box filled with Houghton’s paintings has languished, unseen, since she exhibited them for the first and only time in London in 1871. How they fetched up in Australia, nobody knows. The Courtauld’s rediscovery is an event of tremendous art-historical significance. Not just because Houghton predates Kandinsky and Mondrian by half a century, but because her motivation throws so much clear light on their motivation.

All the famous pioneers of abstraction — Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian — were spiritualists and followers of Madame Blavatsky and her cult of theosophy. But in all their cases, the occult aspect of their creativity has been actively suppressed in the canonical story of modern art. Potty spiritualist imaginings have never been allowed to disturb the smooth progress of progress. On this astonishing evidence, however, the potty spiritualist imaginings were the key ingredient.

I would go further than that. The rhythms of Houghton’s extraordinary watercolours — the dots, the swirlings, the sense of a veil separating one world from another — are fiercely reminiscent of various kinds of ancient rock art. Of Aboriginal art. Of South African cave painting. Of the geometric markings at Lascaux. We are learning something crucial here, I suggest, about the origins of all art, and the insistent templates for it that survive in the collective unconscious. A crucial show.

While the Courtauld is rewriting art history, the Zabludowicz Collection is continuing the more modest task of providing young artists with a forum. As it happens, I have encountered Victoria Adam before, having seen her graduation show at the Royal Academy Schools in 2015. She was really good there. She is quite good here.

Her talent is for identifying and exploiting grungy sculptural materials, scruffy stuff that art would usually ignore. The centrepiece of this tiny display is a large plastic curtain of the kind that gets pulled across dying grandmothers in a hospital. The curtain is covered in what appear to be wriggling earthworms. They are actually petite ceramic sculptures that twist and squidge like earthworms.

So, hygiene is being invaded by biology. Without being able to put your finger on a single specific thing being said here about modern death, your senses know immediately this is the subject being tackled.

Watch Victoria Adam. She will rise and rise.

Georgiana Houghton, Courtauld Gallery, London WC2, until Sept 11; Victoria Adam, Zabludowicz Collection, London NW5, until July 17