Batten down the hatches. I’m afraid they’ve let me back onto the telly. Heading your way is my new four-part series for the BBC, The Renaissance Unchained, in which I barge my way through art’s greatest epoch, pointing out how it has been misrepresented to us, and how it is time we viewed it differently. We’re not talking nuances here. This is a big rewrite, and it involves showing lots of paintings by Hieronymus Bosch.

My point, in a nutshell, is that the Italians stole the Renaissance. In particular, a jingoistic Florentine multi-tasker called Giorgio Vasari, who was both an awful painter and a feisty writer, managed to point art history in a hugely misleading direction when he published his famous Lives of the Artists in 1550. It was the first art-history book. And, therefore, the most influential art-history book. Not only did Vasari invent the term “Renaissance” in this momentous tome, he managed, also, to set the agenda for all the art history that followed. To this day, we view the Renaissance as a largely Italian achievement, during which the great artistic examples of the classical world were rediscovered and matched. Vasari’s fantasy lives on.

Here, then, is a question: which painting technique has had the greater impact on art, oil paints or fresco? And here’s another question: who in recent times has inspired more followers, Michelangelo or Hieronymus Bosch?

In both cases, the answer is clear. When it comes to developments in art, oil paints, pioneered by Jan van Eyck in Bruges in the 15th century, have been immeasurably more impactful than fresco, the technique of choice on Italian walls in the age of Michelangelo. From Rembrandt to the impressionists, from Vermeer to Van Gogh, from Delacroix to de Kooning, oil paints have changed the course of art. Fresco, meanwhile, has died an inglorious aesthetic death.

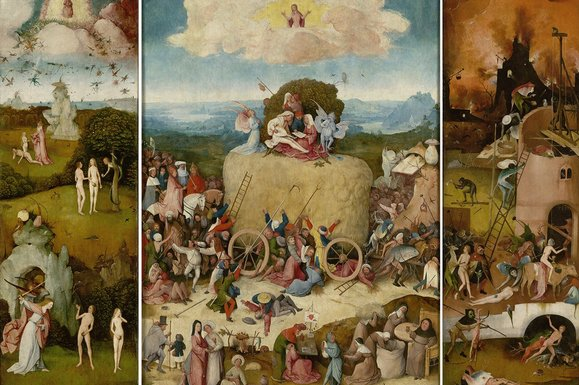

The answer to the second question is just as obvious. Bosch wins hands down. His influence on symbolism, expressionism and, above all, surrealism has been galactic. Without him there would be no Goya, no Dali, no Magritte, no Beckmann, no Chapman brothers, no warpings, no mutations, no dark and violent envisionings of hell on earth. Any art that presents reality as the site of madness and distortion can trace its lineage back to the inventive artistic firebrand born in ’s-Hertogenbosch, in the Netherlands, in about 1450.

This argument of mine that artistic developments in northern Europe had a more profound and long-lasting impact than events in Italy is about to receive some unexpected support from my old buddies, the Fates. With The Renaissance Unchained perhaps in mind, the Fates have kindly arranged for ’s-Hertogenbosch (or Den Bosch, as it’s more commonly known in this linguistically simplistic age of ours) to commemorate the death exactly 500 years ago of its most famous son with the largest celebration of his work the world has seen.

The Bosch extravaganza will be centred on an exhibition that has somehow managed to bring together 20 of his paintings — a huge achievement. His influence was enormous, but his pictures are rare. To gather 20 of them in one display is a triumph of diplomacy and persuasion. There will also be drawings, prints, films, talks, musical concerts, canal rides and city tours, as the fabulous little town of ’s-Hertogenbosch, in Brabant, sets about remembering one of the most extraordinary contributions anyone has ever made to art.

His real name was Jheronimus van Aken. He was called Bosch after his home town, just as Veronese was named after Verona and Leonardo after Vinci. Bosch actually means “forest”, which strikes me as poetically appropriate. The van Akens were a family of painters who had dominated the art trade in ’s-Hertogenbosch for generations. Bosch’s father was a painter, as were four of his uncles. Rather than seeing Hieronymus as an eccentric one-off, we should see him as the leader of a community of artists, among whom he was the most talented.

All this is about to be made clear to us in the once-in-a-lifetime Bosch extravaganza. A word of warning: leave plenty of time to see it all. Having spent the best part of two years attempting to tackle him for my series, I pass on to you the advice that there is no quick way to experience his work. He may only have painted about 15 of his celebrated triptychs, but each of them contains enough detail to keep you transfixed for a week. When we filmed his masterpiece, The Garden of Earthly Delights, in the Prado, we spent more time on this one picture than we had previously needed to film the entire Sistine Chapel!

In every corner, under every bush, behind every rock, something startling is happening. It’s true of all his locations, but it’s particularly true of his speciality, hell. Lots of artists have had a go at envisaging hell. None has thrown themselves into the task as enthusiastically as Bosch.

He keeps popping up in The Renaissance Unchained, partly because his paintings are so exciting and photogenic, but also because he is a Renaissance artist who is hardly ever accepted as a Renaissance artist. Even in the paperwork for the ’s-Hertogenbosch beano, they refer to him as a “medieval” artist, as if they fear there was something outdated about his contribution. In fact, he was almost an exact contemporary of Leonardo, born just a year or two earlier. The Garden of Earthly Delights — which won’t be travelling to ’s-Hertogenbosch, supposedly because it is too fragile, but really because it is the most popular painting in the Prado and they don’t want to be without it — was painted at more less the same time as the Mona Lisa. Bosch was a Renaissance artist all right.

The trouble is that the things that happen in his paintings — the crazy imaginative leaps, the amazing details, the impossible contradictions — are not generally admired as Renaissance qualities. Vasari has seen to that. Any view of the Renaissance that presents it as a return to civilisation, or a triumph of order, has no hope of understanding Bosch.

His other problem is that his art speaks so vividly to the modern world that the modern world keeps trying to understand him in silly modern ways. All kinds of potty explanations have been put forward to unpack his imagery. The mind bandits have had a field day. “One recognises the tragedy of an impotent man who dreamt and fantasised endlessly about all kinds of sexual pleasures, but whose punitive superego, severe castration fear, and sado-masochistic pregenital fixation most likely prevented him from having normal lusty sexual relations,” opined the energetic Freudian Erika Fromm. Another popular suspicion is that he was a user of hallucinogenic drugs — Renaissance LSD! Then there is the recurring suggestion that he was a member of a secret cult, the Adamites, Renaissance hippies who promoted free love and copious sex.

What all these desperate nonsenses have in common is a refusal to accept the less glamorous truth that Bosch was a fervent believer whose art was intended as a pictorial sermon, warning us of the outcome of lust and sin. Frankly, anyone who has actually read the Bible, and in particular the Book of Psalms, will quickly recognise the origins and textures of his imagery.

The hell he paints — the monsters, the fires, the distortions, the tortures — is the hell I remember being threatened with in sermon after sermon, Mass after Mass, in the five terrible years I spent being educated in a Polish Catholic boarding school. On the outside doors of The Garden of Earthly Delights, he has actually written a direct quotation from Psalm 33: “He commanded and they were created.” God made us. Yet look how we thanked him.

This, then, isn’t Renaissance LSD or secret cult talk or sexual impotence manifesting itself as a pregenital castration complex. This is hardcore Christianity, so fierce and obvious that only a myth as powerful as Vasari’s myth of the rebirth of the classical world could ever have blinded us to it.

Hieronymus Bosch — Visions of Genius, Noordbrabants Museum,’s-Hertogenbosch, Holland, from Sat until May 8; The Renaissance Unchained, BBC4, from Feb 15