You have to feel sorry for Barbara Hepworth (1903-75). She was unquestionably one of the greatest artists Britain has produced, and quite possibly our finest sculptor. She was distinctive, powerful, intuitive, inventive. Yet the poor woman seems fated never to be allowed to possess her own identity.

When she was alive, she was understood initially as part of the great marital double act of Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. Later, she was understood as part of the great sculptural double act of Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. Since her death, she has been understood as — well, you tell me.

As I snaked-and-laddered my way through the convoluted Hepworth retrospective that has opened at Tate Britain, the real Barbara Hepworth refused, unexpectedly, to heave into view. It was unexpected because this was the first Hepworth retrospective at the London Tate for almost 50 years, so it was surely going to clarify her presence? But no. “Too often Hepworth has been considered in relation to other, generally male, colleagues,” complains the catalogue, rightly. Then the exhibition itself goes out and does exactly the same thing.

The first room is devoted not to Hepworth as such, but to a moment in British sculpture when “direct carving” became all the rage. In the 1920s and 1930s, direct carving — cutting figures out of a block of stone or a lump of wood — was seen as the purest, most challenging way to make a sculpture. Artists working with bronze or clay could shape and reshape the material till they got it right; with stone carving, if you made a mistake, that was it. And in a macho understanding of these things that goes back to 1550 (when Giorgio Vasari published the first art history book, The Lives of the Artists, and devoted much of it to Michelangelo’s famous struggles to release the figures “hidden” in his marble blocks), stone carving was seen as a primary test of the artist’s abilities.

Maybe. But plunging us straight into the controversy about who favoured such carving, and when, is no way to start a Hepworth retrospective. She’s present somewhere in the clusters of sculptures by John Skeaping, Jacob Epstein, Henry Moore, Alan Durst, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Eric Gill, Elsie Marian Henderson and Ursula Edgcumbe, but where?

Forced to play “hunt the Hepworth”, and to puzzle about issues of “direct carving” for which the groundwork has not been laid, your average museum visitor can have little hope of knowing what the show ahead is about. If this were an exhibition about the “direct carving” moment in British sculpture, fair enough. But it isn’t. There, in a nutshell, you have the problem with the exhibition-making in the Penelope Curtis era.

Curtis, the outgoing director of Tate Britain, has co-curated the display herself, with the Tate’s resident Hepworth expert, Chris Stephens. Having lost us with its confusing opening, the show continues the process in the second room, devoted to the work Hepworth made jointly with Nicholson. Eh? What was that about considering her in relation “to other, generally male” artists? As it happens, the Nicholson room is the show’s finest. Taking its cue from two charming photo albums displayed here for the first time — one his, the other hers — the busy gallery reveals how they inspired and prompted each other on an intimate domestic level.

They met in 1931, when Hepworth dumped her husband, John Skeaping, and Nicholson moved in with her in Hampstead. The intensity of their relationship seeps into all the art they made at the time. In Nicholson’s work, Hepworth’s strikingly pointy profile keeps appearing and reappearing in Picasso-ish paintings in which the cubism looks faded and worn, as if it has been left out in the rain. Hepworth, meanwhile, spurts mysteriously before our eyes into a sculptor interested in abstract shapes. In the first room, she is sculpting animals, torsos and seated African nudes. In this room, she’s sculpting curious blobs and uprights.

The origins of these suddenly sensuous and abstract shapes appear to have been sexual. Two Forms, carved from pinkish alabaster in 1933, features the interlocking of a form that is thrusting and pointy with one that is enclosing and soft. Had the caption not mentioned the phallic symbolism, I would probably have missed it, but once noticed, the intimate origins of Hepworth’s sudden abstraction can never again be unnoticed. What a lot of uprights there are in her work. And what a lot of holes.

Fascinating though it is, the Nicholson-Hepworth room is no help when it comes to supplying the show with a direction. Indeed, it adds to the confusion. On its own, it would have made a perfect display. Embedded in a retrospective, it leads us up another ladder and down another snake.

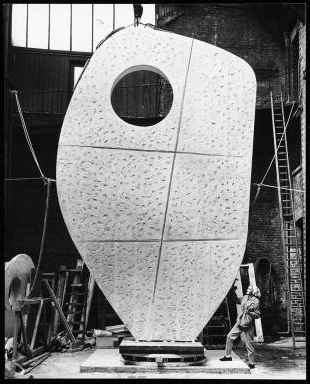

The next section, labelled International Modernism, features the first of the “stringed” and painted hollowings that became her trademark. They’re gorgeous. But instead of encouraging us to enjoy and investigate them as single sculptures, the show sets us the conundrum of trying to work out why they are surrounded here by a line of art magazines of the 1930s that have been stuck up on the wall, all the way round the room, at wheelchair height. Too low to read, too high to be a skirting board, what is the point of them?

And so it goes on. Confusing and tangential curatorial ideas keep getting in the way of the art. Three-quarters of the way through, Hepworth makes fully evident what is wrong with all this in a photograph she took of her own work. It’s those interlocking blobs again, Two Forms, from 1933, photographed on a windowsill where firm, strong shadows can clarify their shape. Eureka. At last, a sculpture in the show is being treated as a sculpture, and not as part of some showy curatorial deconstruction.

At the Gagosian Gallery, Richard Prince has been getting it in the neck for taking images from Instagram feeds, reprinting them on large canvases and presenting them as a new body of work. “He’s stolen someone else’s imagery,” the harpies scream. Rubbish. Prince is doing what artists have always done — taking something from the world about them and reframing it in an art context. Monet didn’t invent poplars or water lilies. He invented ways of seeing them.

While we’re at it, the same is true of Carsten Höller at the Hayward Gallery. The slides he has appended to the wall of the building are tremendous fun to go down, and frame an experience many of us have not had since we were children. Höller didn’t invent slides. He didn’t invent exhilaration. But by framing exhilaration in this new artistic context, he is making viscerally evident how it is missing from our daily lives. Bravo to him. His critics, meanwhile, really need to do some sliding.

Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World, Tate Britain, London SW1, until Oct 25. Richard Prince, Gagosian Gallery, London W1, until Aug 1. Carsten Höller: Decision, Hayward Gallery, London SE1, until Sept 6