Ever since Tate Modern opened, in 2000, there has been one exhibition I have been hoping to see here. Now, finally, it has arrived.

There are many reasons to look forward to a show devoted to Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935). His story was extraordinary. His times were crucial. His inventions were unlike any that came before. But, for me, what really counts is the spirit of his work: its relationship to modernity. Malevich’s art sums up what being modern was truly about.

Now, being modern means almost nothing. It’s the shape of a coffee table; the cut of a trouser. But in Malevich’s day, at the very beginning of the modernist age, it was something violent and hardcore. When Malevich painted his most notorious picture, a black square on a white background, being modern was an act of aesthetic terrorism: one way of picturing the world was seeking to destroy another way of picturing the world.

You can judge for yourselves if he succeeds about a third of the way through this event, where Black Square awaits you like the gaping jaws of a crocodile: so dark, so looming. Painted in 1915, it consists of exactly what it says on the tin — a black square on a white background. Searching for any of art’s traditional values in this shockingly blunt square of geometry — for beauty or depiction or grace — is entirely pointless. They’re not there. As the caption writers of Tate Modern’s pulse-quickening celebration of Malevich’s career rightly put it, Black Square marks “the zero hour” of modern art.

Although he is thought of as Russian, Malevich was born in Kiev in 1879. His parents were Polish and he was brought up a Catholic. From the start, therefore, he had an instinctive understanding of symbols, particularly the cross, which makes recurrent appearances though the show in various abstracted guises.

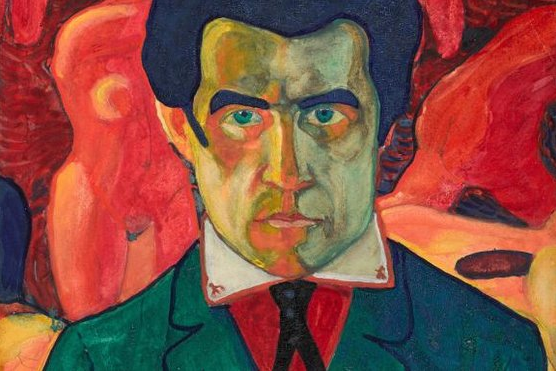

By the time he arrived in Moscow in 1904, and began some proper art training, he was already in his mid-twenties. The opening room fast-forwards us interestingly through his early leaps between styles. The strangest of the early pictures are the religious scenes, golden and decorative, in which deceased Christian saints turn crazily into floating Buddhists. (That will be the influence of theosophy: see my review of the Mondrian show at Tate Liverpool for more on this matter.) But he could do realism, too, as an early portrait of his wild-haired father makes perfectly clear.

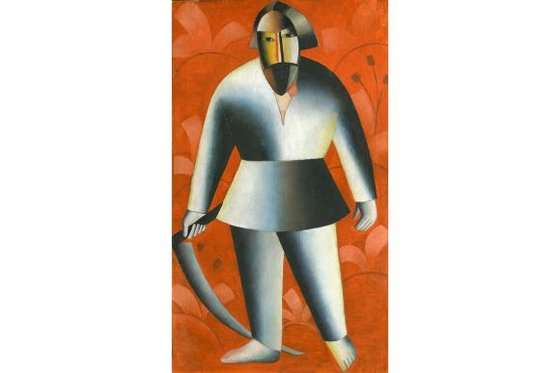

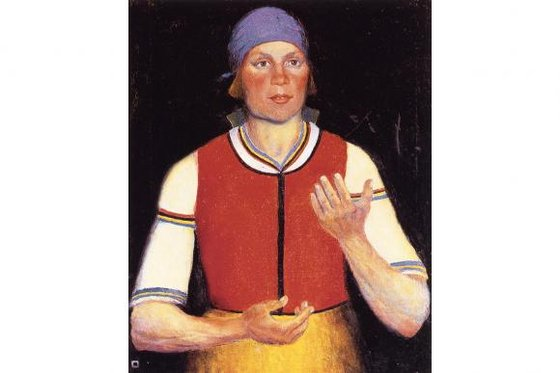

You get a sense, though, that he couldn’t wait to plunge into all the new art styles that were then arriving in Moscow. First, he’s a fauve, then a cubist, then a futurist, then an admirer of Léger, until, circa 1912, he pops out of the Kenwood as a fully mixed Russian modernist, flavouring his work with bright folk-art colours and bold peasant simplifications. These cubo-futurist pictures — Malevich’s term, not mine — are set in the villages of traditional Russia, but the woodcutters, mowers and farmer’s wives have been given outlines and colour schemes that belong on a new tractor: bright, hard-edged, shiny.

It’s rousing stuff. What’s impressive here isn’t just the experimentation itself, but the speed at which it is undertaken. All these spiky pictorial influences must have been clattering down on early-20th-century Moscow like a hailstorm. But I had the feeling as well that there was something unnatural about Malevich’s rate of progress.

All the way through his career, you sense you are in the presence of a loose molecule, a particularly jumpy talent that works in spurts and explosions. When the Black Square suddenly looms up before you, in 1915 (the original painting is too fragile to travel, so it is represented here by an identical version produced by Malevich in 1923), it seems to do so without the appropriate foreplay. Nothing until now has prepared you properly for its arrival.

Extreme pictorial severity. Blackness as a colour that weighs a ton. Nothing and everything represented simultaneously. This really is something new in western art. As I stood in front of the weighty square, I found myself reminded of the ka’aba, the blank black cube in Mecca towards which every dutiful Muslim is instructed to pilgrimage. Those of a more scientific bent may wish to imagine a black star as a parallelogram. What counts here is the powerful sense that the blackness is the focus, the gathering point, for all the incoming forces.

Remember the date, too. It is surely significant that Black Square was painted in 1915. Right now we are commemorating the outbreak of the First World War. Commentator after commentator has sought to underline the particularly dark and hopeless nature of that conflict. And, although the Black Square cannot be understood as any kind of illustration of the First World War, its radical nihilism, that sense here of nothing being relevant except extreme blackness, is surely a response to the times. The old rules have been destroyed. The new rules are being written. This is modernism in its purest and most original form: black, fractured, extreme, nihilistic. Good luck to you if you’re trying to design a coffee table based on those parameters.

As I said, the show keeps jumping in unexpected directions. The abstract art that follows Black Square seems as much an alternative to it as a continuation. It is also astonishingly, heart-warmingly, gasp-makingly beautiful. The two rooms filled with what Malevich christened suprematism — he did like his isms — are two of the most exciting spaces I have walked into at Tate Modern.

Describing this as “geometric abstraction” is like describing the young Brigitte Bardot as “a Frenchwoman”. It’s true, yes, but it gives no sense of the ravishing emotional impact. Rectangles, triangles, circles, interceptions — coloured blue, red, yellow, green — dance about on pure white canvases like acrobats at a circus. They float, they cluster, they swoop. Where the Black Square seems to weigh a ton, these airy bits of coloured geometry appear weightless and shifting, like the patterns at the bottom of a kaleidoscope.

The hang tries to re-create the original cluttered impact of Malevich’s hangs, and how thrilling it is to recognise so many of the paintings here from the touching black-and-white photograph that survives of their original exposition. The curators have had to scour some obscure and distant Russian museums to discover all this, and their reward is an exceptionally successful stretch of the show.

Straight afterwards, though, the journey becomes chaotic again. It’s Stalin’s fault, not the curators’. To its credit, the exhibition as a whole wears its politics lightly. Most displays of Russian art of the revolutionary period get bogged down in dense documentary material describing this Five Year Plan or that. But the present event puts Bolshevik history on the back burner and happily foregrounds the art. Stalin, however, is unavoidable. The Stalinist decision to brand abstract art as decadent and western, and to make social realism the official state style of the Soviet Union, had awful consequences for Malevich’s career.

The whole show appears to judder. Where most artistic careers ebb and flow, Malevich’s halts and starts like a car at the traffic lights. The curators try to make something interesting of the intense theoretical decade he spent teaching art in assorted Soviet outposts, but after what we have just experienced with his glorious suprematist paintings, the dense graphs and carefully explained correlations of his teaching years feel like homework.

Fortunately, there’s a sudden and fascinating coda. Out of the blue, for reasons no one here manages adequately to explain, at the end of the 1920s, Malevich begins painting figurative pictures again. Most of them portray his beloved peasants at work in the fields. But these are no ordinary Russian serfs: these are suprematist serfs, with blank ovals for faces and busily striped abstractions instead of fields. It’s very strange art.

If you look into the background of the lovely Head of a Peasant, from 1928, you can see warplanes strafing the fields and the tiny outlines of familiar Malevich crosses atop the distant village churches. So he’s painting in code. That’s clear. What he’s telling us remains totally, thrillingly, typically unclear.

Malevich: Revolutionary of Russian Art, Tate Modern, London SE1, until Oct 26