There are, of course, many Londons. It’s such a fertile sprawl — so multifarious, alive and active. Recently, the London that has had most of an airing is the one that gets brought out specially for the tourists: the London of happy marathon runners and rousing Olympics; of big royal birthdays and grand state funerals. London in its Sunday best. Most of the time, it doesn’t look anything like that, as Leon Kossoff makes clear in a suite of magnificently dour and grotty London landscapes that have gone on show at the Annely Juda gallery.

In my book, since the passing of Freud and Hamilton, Kossoff is probably Britain’s finest surviving artist. He was born in 1926, in Shoreditch, the son of Jewish immigrants from Ukraine. So not only is he a lifelong Londoner, but he was also an eyewitness to all that political darkness that was the 20th century’s special gift to history. Like Freud, like Bacon, his art seems to harbour the spirit of his times. So no, it isn’t cheerful. Annoyingly for Kossoff — I would imagine — he is almost invariably twinned in our art-historical imaginations with his fellow north London gloomster Frank Auerbach, and has duly had some difficulty gaining the independent recognition he deserves. Both artists are famous — even notorious — for using unreasonable quantities of paint. But when Auerbach trowels on the paint, you sometimes feel it is a question of style. That is never true of Kossoff. When Kossoff trowels on the paint, it is always because that is what is needed to convey what he wants to convey. For me, he is the more inventive colourist of the two, and his glumness is more gripping.

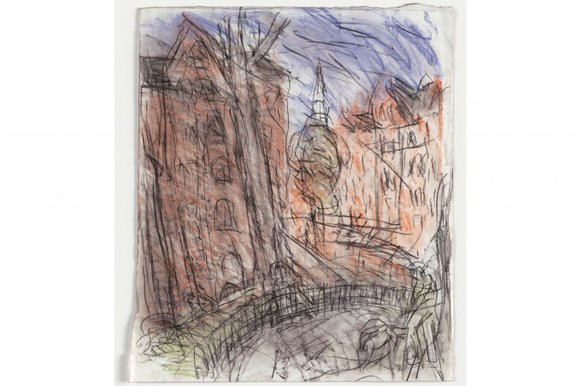

This show consists of lots of drawings, interspersed with a dozen or so dense and hefty paintings. The drawings are full of energy and weather, and buzz about the London streets like a kid on a bike. The paintings are a greater achievement and do something else. Caked with layer upon swirling layer of tarry oil paint, they are so thickly splattered, they stray into the outer margins of sculpture. This is art that seems actually to shovel raw London sensations into you, and then swirl them about, as if you were a concrete mixer hired from Murphy’s.

A map at the back of the catalogue locates every view in the show in the thin interstitial belt of north London that stretches from Bethnal Green in the east to Willesden in the west. This is the London — armpit London? — in which Kossoff has always lived and which he knows so well. It’s not a pretty location. The Queen will never ride through it in the royal coach. Oxford and Cambridge will never race their boats along its canals. However, countless generations of immigrants have grown up in it; and when Kossoff portrays them — which is pretty much in every picture — he turns them into human weeds searching for somewhere to root.

I was lucky to see his paintings in a perfect evening light in the beautifully toplit upstairs galleries at Annely Juda. It made them feel less gloomy than they appear in reproductions, and also made clearer what a visceral colourist he is. There’s a pale blue he uses that makes me want to stick out my tongue and lick it. And a washed-out pink that smells exactly of Victorian brickwork. To be a great colourist, you don’t need to reach for bold yellows and blues, Van Gogh-style. Kossoff is a master of mossy greens, instead; of dirty greys and grubby browns. His colours seem battered and faded, rained on and stepped across. Getting them exactly right, finding this much fugitive beauty in them, is the work of a master.

A particularly splendid painting from 1999-2000 shows that doomy slab of London baroque, Christ Church, Spitalfields, built by Hawksmoor in the 1720s and fated, thereafter, to appear distinctly sinister. Someone once said of Hawksmoor’s churches that you can imagine funerals taking place in them, but not weddings. How true. It was near the famously doomy Christ Church that Jack the Ripper plied his trade. Kossoff paints its great pale mass wobbling and lurching on the roadside like an East End drunk after a few Special Brews. The spire careers up into the sky in bold thrusts and flashes of white. It’s such an exciting picture. And how beautifully it captures the surprising lightness of all that Portland stone, and the lovely relationship it enjoys with the weak sunlight of east London.

So these aren’t just cityscapes. These are portrayals of a state of mind. Kossoff’s London comes at you in all weathers, from all angles, with relentless movement and energy. In the big view of King’s Cross station from 1998, the passing crowd shimmers and throbs like a bag of Mexican jumping beans. In 1972, he discovered the indoor pool in Willesden, where he took his son to swim, and crammed so many people into it that you can barely make out the water.

The show ranges from paintings done in the 1960s to drawings made last year, and all of them feature this turbulence. Roadworks at every junction; cranes on every horizon; construction on every corner. How curious that pretty much all the artists who paint like this — all the great expressionists of the city in flux — are Jewish exiles. In particular, I’m thinking of Chaim Soutine, who seemed every bit as incapable as Kossoff of painting a straight line.

Where so many contemporary art shows these days feel like Tate satellite events, this display has a stubborn distinctiveness to it. Someone who really knows London is showing us something about the city that is really worth seeing. London Landscapes has been curated by Andrea Rose, the director of visual arts at the British Council. She’s the woman who organises the British contribution to the Venice Biennale — the biggest event in art — which is coming up at the beginning of next month. Unlike most occupants of her sort of position, she is acute, brave and, above all, independent. We should clone her.