Jenny Saville has had a strange career. There is no doubt that she is an exciting painter, whose pictures wobble and throb with fleshy vitality, but the strange trajectory of her career has made it impossible to keep up with her. One moment, she was everywhere. The next moment, she was gone. Indeed, until this new selection of her work popped up at Modern Art Oxford, I have not had cause to think seriously about her for a decade and a half. Every now and then, I would wake up and wonder fuzzily: Jenny Saville? Is she still out there? But it was never an urgent inquiry.

We now learn that two of the great shaping forces of humanity were responsible for her disappearance. One was motherhood, which we will come to, because it is the focus of her latest work. The other was money. Perhaps I should rephrase that more pleasantly as “the dynamics of the art world”. Nah, that is too kind. The filthy rich have hogged Saville. Ever since the pioneering Charles Saatchi discovered her in the early 1990s, and press-ganged her into the movement formerly known as the YBAs, now known as the MABAs, she has been fiercely collected by the Saatchi buyalikes. As soon as she finished a picture, she sold it. The rest of us never saw her art, because Saville became a brand that only the rich could afford. Thus, her impact has been wasted on hedge-fund managers and collecting power couples from Miami.

She is not alone, of course. British art in the Frieze years has witnessed a number of these Mary Celeste careers that have slipped past us, unseen. Glenn Brown. Cecily Brown. Paul Noble. None of them has played the active role they should have in the shaping of British art because all of their careers have been acted out in private. They’re the private dancers, dancing for money, who’ll dance what the Gagosian Gallery wants them to do. Saville’s case is the most frustrating, because her example is so forceful and feminist. She really could have made a difference. Anyway, she’s only 42, so perhaps the years of proper involvement lie ahead. What is sure is that the artist we encounter now at Modern Art Oxford has painted some of the most bellicose woman’s art of our times. She doesn’t always get it right, but when she does, it’s like being thrown into a cage with a gorilla.

Saville’s paintings go after you. This is art so physical, you can feel its hot breath on your face and hands. If you try to back off, it fixes you with burning eyes and telepathises something deep and crucial into your thoughts. It’s obviously a big personal message. But you don’t speak gorilla, so the nuances are lost on you. Sadly, the Oxford show is not a full retrospective. Neither is it a selection of new things. Instead, it’s a mildly unsatisfactory hybrid of the two. The oldest work dates back to Saville’s noisy emergence in 1993, when Saatchi plucked her out of the Glasgow School of Art and imprisoned her in a tower to paint for him. The spooky image of a naked female back that caused a stir at the Sensation exhibition is here again: the one in which the marks left behind in the flesh by the woman’s bra and pants are displayed to us like evidence at a wife-beating trial.

Saville’s fascination with the fat female body is said to date from a work placement she enjoyed as a student in Cincinnati. Something about the shamelessness of the American fat girl struck a chord with her. Fulcrum, from 1999, is fully 16ft long. It shows three extra-fat naked bodies lying on top of each other, forming the fleshiest, full-length, full-fat sandwich in art. There are mountains in the Rockies that take up less space than this massive blob of intertwined feminine nudity.

As a result of all the practice she has had, Saville is the best painter of the female nipple I have seen. She gets them perfectly. She is also a master of the bulging thigh and the overhanging belly. Compared with the enormous flesh fests gathered in this show’s back room, the art of Rubens is a celebration of anorexia. Yet, perversely, it is the fierce gazes peering out from all this excellently captured cellulite that actually pin you to the wall. Every painting here has the air of a dare about it. First, it dares you to look. Then it dares you to disapprove.

To reach the old pictures at the back, throbbing with fleshy female anxiety, you need to pass through a suite of recent drawings concerned with motherhood. It’s a mildly unsatisfactory approach, only because the new drawings strike a domestic note and are merely very interesting. The art gluttons among us would have preferred a proper retrospective, because Saville owes us a banquet, not a selection of snacks.

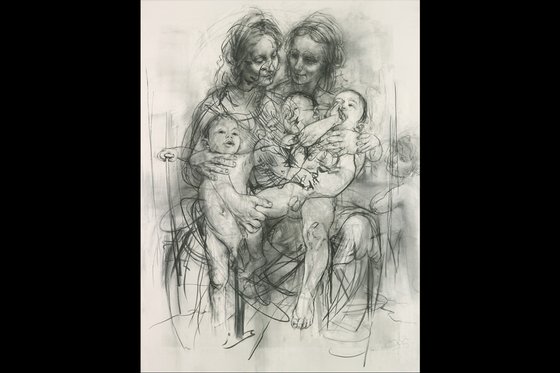

What am I saying? This may not be the most coherent of displays, but it is an unmissable one. The new drawings were prompted by the birth of Saville’s two children, a boy and a girl, who are obviously the other main reason she dipped out of sight. You can tell immediately from the art they inspired that Saville took her motherhood seriously. There is nothing remotely progressive about her naked self-portraits with her children. These are drawings so direct, they could have come straight out of a life class.

What they notice, however, and what male artists recording the same situation always miss, is the amount of movement involved in holding a baby on your lap. In bold, firm charcoal outlines of the kind women artists seem to be so much better at than men — think Paula Rego, think Nicola Hicks — Saville presents a vigorous battle of the torsos between the writhing, twisting, slippery bodies of her children and her own beautiful, bulging, Rubensian presence.

Because this is Jenny Saville, and because her work always nurses an ambition to challenge the male gaze, the motherhood drawings turn quickly into an examination of the way mothers and babies have been presented in art. Study for Isis and Horus (2011) superimposes Saville’s own body and that of her child over the shadowy image of the Egyptian earth mother and her son. There are probably other mothers and kids in art being examined in there, too, but with so much writhing going on in the image, it’s hard to make them out.

You know that famous Greek statue of Laocoön and his sons fighting a giant snake? Those are the sorts of sensations conveyed here. Mirror, a big and particularly busy image of a reclining nude, seems to feature seven or eight nudes going on at once. Manet’s Olympia is definitely quoted in there somewhere, twice, and so is Picasso’s version of Velazquez’s Las Meninas, plus Giorgione’s Dresden Venus, alongside several nude appearances by Saville herself. We are obviously watching a face-off between male fantasies and female reality. But with so many pictures overlapping, the poor piece of paper won’t keep still, as if it is being pleasured by a big vibrator.

Two more of these vibrating old master drawings are also on show at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, where they find themselves surrounded by a fine selection of Renaissance Madonnas and Children. This is lofty company, but the Savilles hold their own easily. They are bigger than the old masters. Bolder. More psychological. Not only do they show off her superb talents as a draughtsman, they seem to be happening much closer to us. A roomful of pretend babies has been invaded by some startlingly real ones.