I opened the catalogue for Tate Modern’s Alighiero Boetti show, read the first sentence, had a good laugh and chucked it across the room. What a waste of space. “The burden of orthodoxies, categorizations and generations fixed in time and sanctioned by art criticism and institutional discourse during the 20th century calls upon a renewed approach to art history,” it flapped. The meaninglessness of such a sentence is offensive enough: how can a burden call upon an approach? But what made it especially annoying was the fact that it was signed jointly by Glenn D Lowry, director of the Museum of Modern Art, in New York; Manuel J Borja-Villel, director of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, in Madrid; and Chris Dercon, director of Tate Modern. What did they all do — take one third of the sentence each? Did the American do the nouns and the Spaniard the verbs?

However the three of them managed to create this unhelpful tosh, they should be jointly ashamed. As the directors of the three national museums that are hosting this travelling Boetti retrospective, they are in the communication business, and to produce a catalogue introduction as comically abstruse as this is, in my book, a civilisational crime. The show they are waffling about so unhelpfully could do with some sensible illumination. It’s a difficult and occasionally tortuous display. I came out of it suspecting that Boetti’s lofty art-world reputation was undeserved and that much of his art was tedious, some of it was silly and all of it was problematic.

Boetti was a familiar artist on the biennale circuit, a curator’s favourite. Born in Turin in 1940, he died suddenly in 1994, and this is the first opportunity most of us will have had to see most of his work together. He emerged in the late 1960s as part of the arte povera movement, Italy’s most influential post-war ism. The first two rooms show him becoming an arte povera artist, then deciding that he wasn’t one after all.

The arte povera tag was invented by the thrusting Italian critic Germano Celant. It means “poor art” and referred to a group of radical Italian artists of the late 1960s, who used humble materials to create bleak conceptual sculpture. Coal sacks were typical arte povera materials. Broken glass. Concrete slabs. At the time, Italian politics was trapped in a destructive cycle of corruption and disruption, and arte povera seemed to rhyme with the national mood.

The opening room duly features a stack of metal girders, a sculpture made from kindling and a brown dome formed from a roll of corrugated cardboard. Cube, from 1968, is a box packed with odds and ends of wood, macaroni, plastic, polystyrene, all levelled off neatly and shown under glass, like one of those pietra dura table tops, made from different types of precious marble, that pop up at Christie’s and cost hundreds of thousands of pounds.

I have always found arte povera to be one of the more helpful art-world labels, because it described something tangible: an assault on catwalk Italy; an attack on false Roman elegance and showy Milanese design. As soon as they began calling Boetti an arte povera artist, however, he began insisting he wasn’t one, and the show ahead makes fully clear that he was too much of an egotist to accept any such grouping. Instead, unfortunately, he saw himself as that most wearisome of post-war art-world figures: a shaman, the artist-magician whose touch turns humble substances into art, and whose insights are presented here as uncommonly profound. Boetti himself makes the shaman identification explicit in a self-portrait called Shaman/Showman. It shows him intertwined with his own full-length reflection, the artist as a kind of mystical Vitruvian figure, with a flame of enlightenment rising from his head.

Less explicitly, but just as worryingly, he spends the next slab of the show turning himself into the subject of his own potty personality cult: casting his signature in iron, spelling out his name in sign language, putting up plaques that celebrate the anniversary of his birth, then the anniversary of his projected death. He even changes his name from plain Alighiero Boetti to portentous Alighiero e Boetti — Alighiero and Boetti. The Maharishi Mahesh Yogi would have been proud of such tremendous self-absorption.

For me, the most telling of the early works is another self-portrait, which introduces us to one of Boetti’s ancestors, an 18th-century Dominican monk called Giovan Battista Boetti, who converted to Islam and became, it says here, the leader of the Chechens in their fight against Catherine the Great! Clearly, this extraordinary ancestor played a telling part in Boetti’s new sense of self, because most of the work that follows can be understood as a touristic response to sophisticated Islamic thinking.

In 1971, he made his first trip to Afghanistan, and continued to make two trips a year there until 1979, when the Soviet invasion made further journeys impossible. In Kabul, he bought a hotel, the Hotel One, a hang-out for hippies and students remembered here in some atmospheric photographs, and he began to commission his best-known works: a series of maps of the world in which the outline of every country is filled in with the relevant national flag.

These famous maps were painstakingly woven by teams of Afghan women, overseen by a male foreman. I don’t know how much Boetti paid the women for the eye-busting, finger-thickening, never-ending labour that went into the creation of the maps, but I do know how much they now cost at auction. As exploitation, it’s not in the Nike class, but it still pongs of sweatshops and colonial instruction.

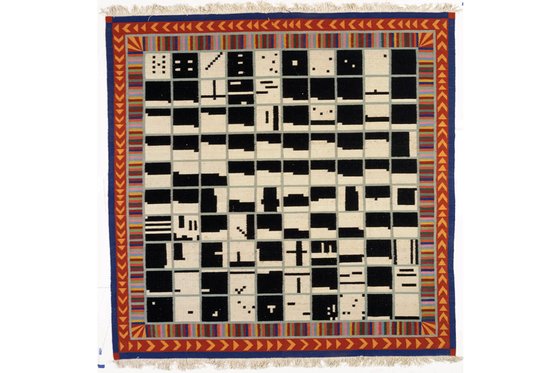

Having been helpfully chronological until now, the display fragments into dense thematic clusters. One room is given over to a puzzling pixel game played out with repeated squares in a grid. Another looks at art created by sending things in the post. A third celebrates the circuitous puzzle of time with a light-bulb sculpture that switches on for only 11 seconds, once a year.

I kept feeling I was being confronted by a world-view learnt in an ashram, and a mood that fluctuates from ersatz Buddhist to ersatz Islamic. Boetti’s Biro drawings, for instance, again manufactured by indefatigable assistants, this time in Italy, are clearly an attempt to transpose the Afghan weaving methods to ballpoint pen. Instead of weaving each individual stitch, the Biro drawings replace it with a Biro mark, hundreds of thousands of them, all laboriously applied by hand so that the overall effect feels fetchingly uneven and not unlike a deep blue kilim. Hidden within the Biro drawings and map weaving are esoteric messages transmitted in simple word codes. One Biro drawing secretly spells out the message: “Bringing the world into the world.” While the translation of the Arabic calligraphy contained within the most beautiful of the carpets reads: “The Afghan people consist mainly of Muslims. Their Holy Book is the Koran. They are willing to sacrifice themselves for their Holy Beliefs. For this reason they have embarked on the Holy War.”

Employing more and more assistants, creating more and more maps, making ever larger and more decorative weavings and filling them with ever more esoteric secret signage, Boetti emerges here as a thin talent hiding behind a huge oriental bedspread. Various Islamic ideas about repetition, geometry, the importance of symbols, the deliberate pursuit of imperfection — because only Allah is perfect — find a clunky western approximation in his increasingly irritating output.

His visits to other cultures are aesthetic day trips and the impression of depth is preferred too often to depth itself. His final self-portrait, completed just before his death, is a life-size bronze sculpture in which he shows himself squirting water onto his head with a hose, so that the flame of enlightenment is continuously extinguished and a cloud of steam rises instead from his overheated brain. Self-knowledge, at last.