Ged Quinn is one of the most entertaining artists at work in Britain. That is obvious. However, just about everything else about this reclusive and distant painter, who lives in Cornwall and keeps himself to himself, is unclear. His mysterious landscapes, packed with mysterious details, seem to be full of mysterious meaning. Yet nobody, except perhaps Quinn himself, will ever be entirely sure what that meaning is. Which is exactly right for the times. Some turn to Harry Potter for impenetrable cosmic plot lines and grand dollops of time-hopping gothic nostalgia. But I’m a grown-up. So I turn to Quinn.

Quinn used to show at the Wilkinson Gallery, in the East End, a habitually enterprising alternative space with an impressive track record of hunting down awkward talent. He has now moved to the Stephen Friedman Gallery, in the West End, a dull place with not much of a track record in anything, but situated poshly in the next street along from Savile Row, so perhaps it was the whiff of fivers around here that attracted him.

Whatever the reasons for the transfer, it has had the immediate effect of boosting the decorative qualities of his work while seemingly lessening its conceptual heft. I can easily imagine someone strolling into Agnew’s to buy a sporting print, detouring to Fortnum’s for a hamper of champers, then popping into the Stephen Friedman Gallery for a quick Quinn.

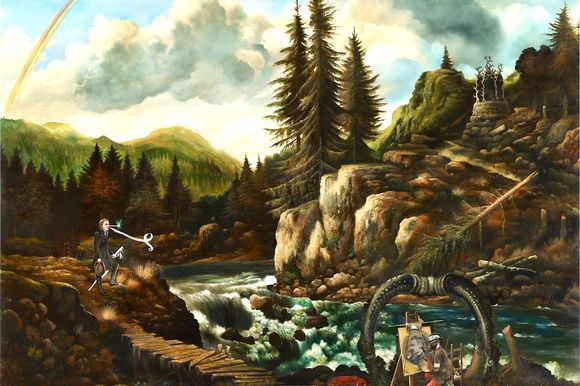

All of which feels like a clear case of misplacement. Because Quinn is not what he now appears to be. At first sight, he passes for a pretend old master: a painter of big and lofty baroque landscapes in the manner of Claude Lorrain, with an added note of turbulent Romanticism in the manner of David Caspar Friedrich; and a sense of epic outdoor theatre in the manner of the Hudson River School. Just as Harry Potter seems to be an amalgam of every nostalgic children’s fantasy written before and during the Billy Bunter era, so the paintings of Quinn appear to paraphrase most of the sizeable achievements of landscape art in the pre-impressionist age. There are even bits of Turner in there. (Quinn should bring out a Christmas board game for keen art historians, Spot the Old Master. I’d buy it.)

In fact, the new show is his best so far. It features half a dozen of the fascinating Lorrain-sized landscapes and a couple of intriguing, if not entirely successful, portraits. As always, the initial impression is of having wandered into a Bonham’s auction and found yourself in a roomful of old masters: bog standard in quality, perhaps, but old masters nevertheless, all painted in a slick and brush-free salon style, the kind that modern art is generally against.

The big landscapes tug you back immediately into an earlier century, the 17th, mostly, but with a bit of the 18th added on. Though that ruined tower on the ruined Flemish rock formation has something of the 15th about it, doesn’t it?

Not even a Martin Scorsese movie chews up quotations quite as greedily as a Ged Quinn painting. But to what end? Why? As you wrestle with this insistent question, the mad sampling seems slowly to gel and even begins to make some sense. Though that, of course, could be another illusion.

The breakthrough clue is the lack of frames. Pictures of this style and size are generally encountered on posh walls inside plush gold ones. Quinn’s pictures are aggressively frameless. This absence of appropriate bordering has the curious and clever effect of adding quotation marks to the experience of encountering his art. Thus, as soon as the first impressions have had their say, a strong sense of contemporary wrongness sets in. Paintings that look as if they are set in the distant past are actually aiming their aggressive disenchantment at the present. We are being toyed with. Skilfully and ruthlessly.

Lorrain, Quinn’s go-to pre decessor in the painting of idealised imaginary landscapes populated with symbolic classical figures, set his mythological mysteries in the Italian campagna, where the soft and golden light of the southern half of the boot boosted the dreaminess of all that it bathed. Quinn’s landscapes are located further north: somewhere darker, gloomier, more angst-ridden. Germany? Alaska? Switzerland? Wherever this place is, you would not want to be wandering about in its woods after dark. Examine these painted beauty spots in any kind of detail and they begin to feel tense and surreal. And that is before you lean in and locate the inhabitants.

Where Lorrain populated his landscapes with classical goddesses and tunic-clad mythological heroes, Quinn goes for serial killers, two-headed mutants, Hitler youth, John Ruskin, misplaced French revolutionaries, monkeys, angels and Jesus Christ after his flagellation. A landscape designed for nymphs and gods has been taken over by Unabombers, mutants and time lords.

In Falling and Being Thrown, the great 19th-century dreamer and art historian John Ruskin stands on a rock by the side of a rushing Germanic stream while a monkey with a paintbrush, borrowed from Chardin, paints a portrait of Nietzsche on another rock. In the foreground, a conked-out goldfinch in a niche, borrowed from Carel Fabritius, has been at the laudanum and has passed out. A thoroughly peculiar, demanding cast, cut and pasted from distant corners of the art-historical road map, has been brought together to act out a thoroughly puzzling pictorial drama.

In the show’s most deceptively religious painting, The Little Boy That Lived in My Mouth, an angel in a forest lays down a rose on a ruined tombstone shaped like one of Male vich’s architectural utopias, the ones he dreamt of in the heady early days of Soviet communism. It takes a moment to realise that the forest we seem to be in is actually an overgrown cemetery based on the Jewish graveyards painted by Ruisdael.

Quinn, you start to realise, is a grumpy critic of the modern world who has chosen to disguise his disappointment in humanity’s progress by dressing everyone in his art in period costume.

A job lot of tragic characters and their symbols, seemingly acquired from the second-hand old-master character-and-symbol shop, have been transported to a mutating Black Forest and forced to act out a dark new fairy tale of loss, corruption and decay.

Malevich’s dream has become a tombstone. Friedrich’s soaring mountain vistas have become the inspiration for Nazi genocide. This is a world in which nothing good happens. Dreams are lost. Nature is corrupted. Utopian ideals are allowed to fall into ruin. Good turns into evil. And a brilliant understanding of the human condition, such as the one arrived at by Nietzsche, is misunderstood by Hitler and turned into the Final Solution. A well-read and wacky mind, one that could probably do with a visit to Herr Freud, is telling us an exceedingly depressing tale before bedtime.

This is impressive art. But what a bleak world-view. No wonder Quinn moved to Cornwall.